After finishing up my time in Romania, I flew Moldovan airline HiSky from Bucharest to Chișinău, the capital and largest city of Moldova. Moldovan airline FlyOne returned me to Prague. Who would have thought that Moldova would have multiple low-cost airlines?! A tour guide told us that flight traffic to/from Moldova has increased markedly since the beginning of the war in Ukraine given the lack of flights and the restricted airspace now. Ukrainians packed the airport when I was there.

Moldova has a long, complex history, and major changes continue to unfold, with lots of junctions and crossroads along the journey. Here’s where Moldova is located, land-locked between hugger Ukraine and kisser Romania:

Before I left Bucharest, I had a tour guide there who grew up in Chișinău. She told us that saying “kiss me now” was a way to memorize how to pronounce the city’s name, which is a stretch, but it gives a sense. Chișinău is a smaller, more pleasant, city than Bucharest, frankly.

Moldova is often said to be Europe’s least-visited country, and perhaps is even the second least-visited in the entire world! That’s a shame, because there are definitely many engaging attractions for tourists, at least for a few days on the ground. Chișinău itself has a beautiful central core full of great restaurants, cafes, and leafy parks. There’s a remarkable lack of graffiti compared to Prague and Bucharest, and street sweepers keep the sidewalks very clean. But I don’t trust the visitor stats, and perhaps they’re just outdated now, as I encountered many tourists, and doing the math, it doesn’t add up to so few. That said, it’s clearly not a heavily touristed destination. I decided to go there because I was already close in Romania and because it feels adventurous to visit former Soviet republics. Moldova was previously the MSSR, but now most in the country wish to distance themselves from Russia, toward the European Union (EU). In fact, most Moldovans are very strongly connected to Romania, having been united and sharing a common language. And the Moldovan flag is based on Romania’s.

This post isn’t meant to be a history lesson, and I don’t want to type it all up, so here’s the last >200 years in a nutshell:

During the Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812), the Russian Empire defeated the Ottomans. The Treaty of Bucharest (1812) forced the Ottomans to cede the eastern half of Moldavia — the land between the Prut and Dniester Rivers — to Russia. Russia named this territory Bessarabia. Western Moldavia stayed with the rest of Romania (then under Ottoman control), while eastern Moldavia (Bessarabia) was part of the Russian Empire. 100 years later, after the Russian Revolution (1917), Bessarabia declared independence as the Moldavian Democratic Republic, and in 1918, it voted to unite with Romania, joining the Kingdom of Romania after World War I. But that didn’t last long, as under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (the Soviet/Nazi deal dividing Eastern Europe), the USSR demanded Bessarabia from Romania in 1940. Romania, under pressure, ceded Bessarabia without major fighting. The Soviets then created the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian SSR) by combining most of Bessarabia with a small part of the Transnistria region east of the Dniester (previously in Ukraine). With the collapse of the USSR, the Moldavian SSR declared independence on August 27, 1991, becoming the Republic of Moldova.

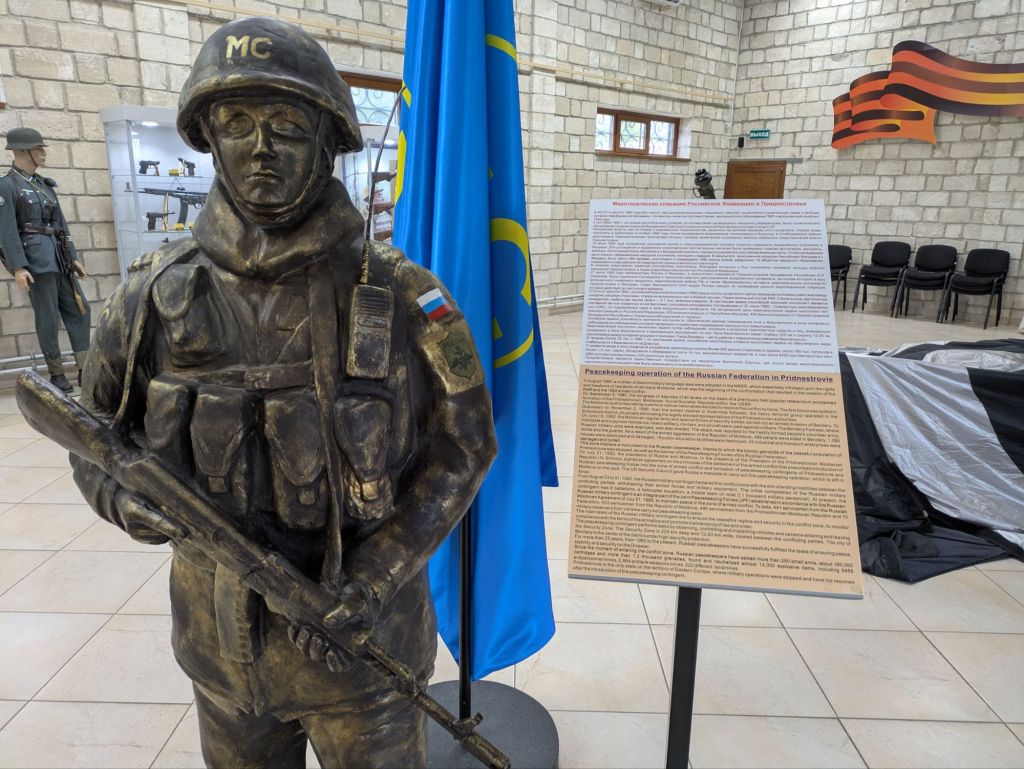

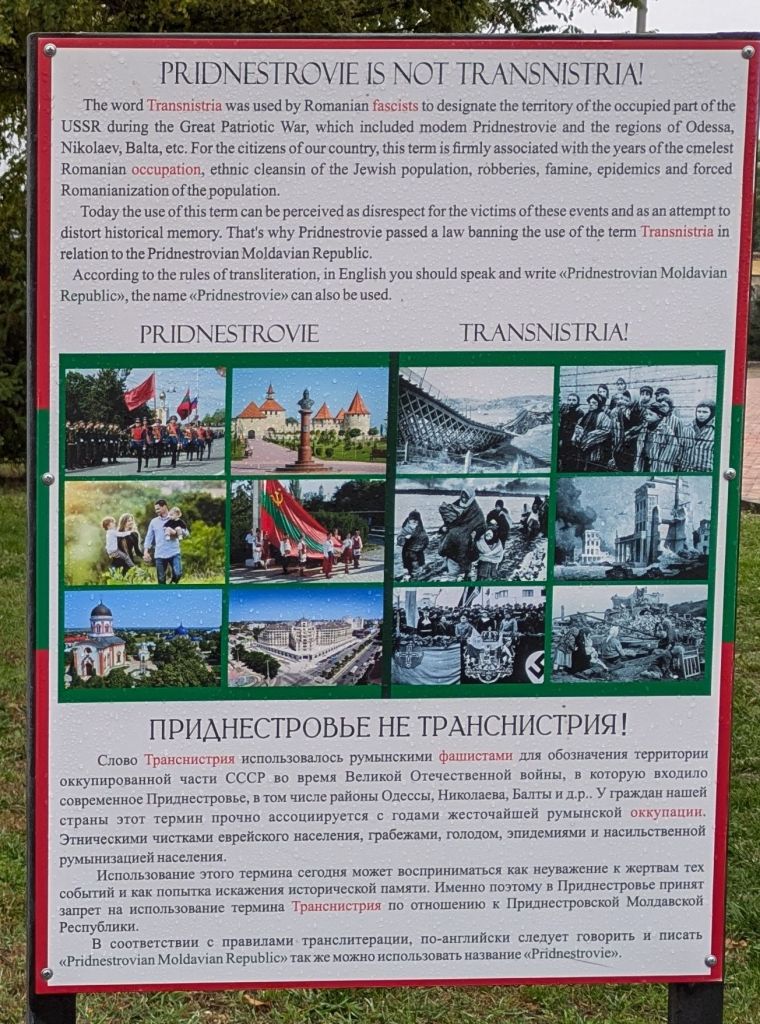

However, that’s not the end of the story, as Moldova retained the region of Transnistria (called Pridnestrovie in Transnistria), where the bulk of the country’s industry was located. Having formerly been part of Ukraine, Transnistria had a large Russian and Ukrainian population, and only a minority of ethnic Moldovans (Romanians). So, unlike in western Moldova, many locals identified more with the Soviet Union and Russia than with Romania. In 1989, Moldova adopted Romanian as its official language, using the Latin alphabet again instead of Cyrillic forced by the Soviets to attempt to create a distinct Moldovan identity, separate from Romanian. But many in Transnistria viewed this as an attempt to “Romanianize” the country, so when Moldova moved toward independence from the USSR in 1991, Transnistrian leaders declared their own “Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR)”, aiming to stay within the Soviet Union (or later, independent). Tensions erupted into armed conflict between Moldovan forces and Transnistrian separatists in mid-1992. Russia’s 14th Army, stationed in Transnistria since Soviet times, intervened on the side of the separatists. Fighting was short but intense, with about 1,000 people killed. A ceasefire agreement was signed in July 1992, brokered by Russia. Transnistria remained de facto independent, with its own government, army, police, currency, etc. However, even to this day it is not recognized internationally by any United Nations country, not even by Russia. While Moldova technically still claims the territory, it has no control over it.

That’s where my story begins… The highlight of my week and a half in Romania and Moldova was definitely a day trip to Transnistria, or “Pridnestrovie”, as the locals insist it be called. Having grown up during the Cold War, and being quite frightened by the prospect of nuclear war with the Soviets, it felt daring to visit a state (even if unrecognized) which still keeps the hammer and sickle on its flag! (It’s the only one in the world.) I’ve by now been to numerous formerly communist countries, including a handful of former Soviet republics, but this felt different because it’s the only formerly communist place I’ve visited where the majority wants to maintain strong ties with Russia (besides Russia itself, haha). Communism, we can clearly acknowledge, was a terrible failed experiment. I understand that there are some aspects to those decades which seem decent in hindsight. But good riddance to the terrors, atrocities, and just general unsustainability of it all. And while Transnistria isn’t actually still communist (and they seem to actually be controlled by a company), there is much nostalgia for the USSR years, for sure. Russia continues to keep several hundred troops in Transnistria, officially as “peacekeepers.” And frankly, their presence does keep the peace. I saw some of these soldiers with their white, blue, and red horizontal striped flag patches. Transnistria functions as a self-governing entity, with its own government, flag, border control, currency (the Transnistrian ruble), vehicle registration, postal service, and even passports. No one can travel outside of Transnistria with that passport, other than to Moldova, haha. And the vehicle registration and license plate doesn’t allow for crossing into anywhere except Moldova. It’s a big commitment for systems that hardly function other than locally. But Transnistria maintains close economic and cultural ties with Russia, with a heavy dependence on Russian energy and subsidies.

Moldova complains that the Russians are occupiers and that their presence is intentional to prevent Moldova’s integration into the EU, and especially NATO. Intentional or not, it certainly does that. Most probably intentional.

I took a day trip there with two other tourists, one from Poland, and a Mexican guy who now lives in London. They were fun to share the unique experience with. We had a Transnistrian driver (Vasilii) who picked us up in Chișinău, and we had to go through a demilitarized zone and then a border crossing to enter Transnistria. We showed our passports and received no stamp, but a small piece of paper providing premission to be in the state for the day. Once in Transnistria, our English-speaking tour guide, Tatiana, (Vasilii didn’t speak much English) met us and showed us around both Bender and Tiraspol, two cities there. Definitely a fascinating visit. We encountered very, very few other tourists during the day there, and the locals seemed mostly indifferent to us, while shopkeepers smiled while practicing excellent capitalism. There were multiple kitschy stores and canteens with Soviet and communist memorabilia lining the walls and shelves. But the ironic thing was that the other customers all seemed to be locals. I suppose they just revel in reliving the past, the “good old days”. What people seem so easily to forget is that while there were some good things back then, the reality was unsustainable – it was going to come to an end, regardless.

I’m always a sucker for any country’s money, and I find it so amazing that Transnistria has their own currency (the ruble) and mint. Not only do they have metal coins, but they also offer plastic-like composite material coins of different colors which look a bit like guitar picks. Credit cards and bank cards from the US and Europe don’t work in Transnistria — so one must exchange euros or Moldovan lei to local rubles before trying to pay for things.

YouTubers now enjoy visiting Transnistria and reporting on what they find. People are people everywhere — good, bad, and ugly. Here’s a heart-warming video from a Swedish-French guy and his Russian-American friend:

But while you’re in Transnistria, don’t call it by that name! Locals call it Pridnestrovie. Transnistria is the Romanian name, meaning “beyond the Dniester”, while Pridnestrovie is the Russian name, meaning “by the Dniester”. I read that it’s illegal, punishable by jail time, to call the breakaway republic by the name “Transnistria”. I was careful to try to memorize the more difficult to memorize name of Pridnestrovie.

In addition to visiting the Soviet era buildings, seeing communist kitsch, and pondering war memorials, we enjoyed an excursion to our guide’s parents’ house for a tasty and welcoming lunch. Her mother made us food, and we drank her father’s homemade wine. What an experience!

Moldova itself pushes toward EU integration, and the country held an important election just before my arrival, where thankfully the majority voted for the pro-EU party, not the pro-Russian ones. Moldova has a female president too, and in the history museum I found a section of a room dedicated to many photos of her with various EU and world leaders.

Our tour guide told us that many Moldovans are switching from the Russian Orthodox church to the Romanian Orthodox church instead, due to the Russian church’s outright support of the war in Ukraine.

Today’s dad joke:

Here’s a short example interaction of an English teacher in the 1970s teaching verb conjugation to a Soviet student:

Student: “You is…”

Teacher: “Is?”

Student: “Are!”

Today’s regional insights:

In every Moldovan restaurant I visited, the server explicitly told me how long I should expect to wait for the drink and for the food to be delivered. Nice touch! I like that tradition.

Coincidentally, one of my Prague running buddies was in Chișinău with a Czech co-worker for a work trip through Czech Aid to help a government-sponsored Moldovan program to increase tomato yields in the country. I met with them for a couple of dinners, and their stories of this experience were educational and interesting. One sees how relevant the Soviet-era science was in Moldova, a very important vegetable-producing region of the USSR, but sadly, now the funding is very low, so progress is a real challenge.

I noticed while in Romania a device that was extremely common. I’m sure I’d seen it before elsewhere, but hadn’t thought about it until seeing it so often while in Romania. Specifically, people there tend not to smoke cigarettes or vape, but instead they use tobacco heating devices. The tobacco is heated instead of burned. People often even get away with using it indoors. There is much less smelly smoke or vapor, as compared to regular cigarettes and vaping products. I’ve since learned that all the big tobacco companies have their own respective brands. For example, the “glo” brand from BAT seems particularly popular in Romania. Ploom from Japan Tobacco and IQOS by Philip Morris are two additional high-selling options. The user takes a specially-made tobacco stick and inserts it into a small electronic holder, which heats the tobacco (to around 350°C, 670°F) rather than burning it. The user then inhales through the white filter tip while the device heats the tobacco inside. The device itself looks like a small clamping or pen-like gadget, sometimes with a button and light indicator. After use of 3-4 minutes or 14-16 puffs, the user removes and discards the used tobacco stick. I’m sure it’s really good for you.

Today’s light-hearted and funny, but simultaneously painful and provocative, video:

My first attempt to comment was unsuccessful, so here’s another try. Great post! UNC has a basketball player this year from Moldova, so I am pleased to learn about it. The adjoining Russia-affiliated pseudo country sounds bizarre, but fascinating. Just another example of the challenges of eastern Europe.

I hadn’t known that there were strong basketball players from Moldova. Amazing how college teams can find these talents all over the world.