Because of multiple Czech holidays during my stay in Prague, the six-week course (30 days) actually takes seven weeks to complete. So my final four days are next week, finishing on Thursday, May 15. At this point, I’m very ready for it to end, but I can certainly see it through. At the same time, I’ve become quite used to heading out at 8am every weekday morning to catch the #6 tram for a 12-minute ride from the Bohemians stop in Vršovice to the Novoměstská radnice stop in the New Town (Nové Město) for a 7-minute walk to the Voršilská building of Charles University (Univerzita Karlova). Then I head upstairs to the study room on the third floor, which I always have to myself, surprisingly. I open the windows, which overlook the Embassy of Mexico across the street. I finish up any residual homework left over from the night before, and then study our new material for the rest of the time (so as to hopefully make less of a fool of myself than I would otherwise) before I head down to the second floor to our classroom, with class beginning at 9am. I’ll have been working with the same eight other students and the teacher for 135 total hours once we’re done. That’s a lot of time together. It’s my new normal now, which I strangely very quickly became accustomed to. But quite soon it’ll all be over, and I may never set foot in that building again, and I’ll possibly never see any of these folks again. I’d like to try to stay in touch with some fellow students, but anyway, it’ll feel odd when it’s all suddenly over next Thursday. And then I’ll get used to that newness.

Someone recently told me that I should feel proud to be taking a Czech course from what is probably the best Czech language program, and at Czechia’s most prestigious university, which is also one of the oldest universities in the world. And that is something, but heck, as a beginner, as long as you pay, they’ll let you attend. And I guess the price motivates students to see it through too. There are more affordable and even free options, but I hear that students in those courses are more prone to drop out. I will feel good about finishing. But I don’t foresee taking another intensive course like this again, for Czech at least. I feel that a good compromise would be to ease off the accelerator, giving myself more breathing room to work and relax more, while still learning the language, but with less intensity, frequency, and duration. Then again, while the 135 hours of class time might sound like a lot, the Foreign Service Institute estimates that I’d need over eight times that many hours of class time to reach “just” a B2 level of proficiency (level 4 of 6). That’s a very long journey, indeed.

I don’t know that any of the other students in my class have signed up to take the next course, which actually begins just the following week. I don’t believe they have, actually. Each student has a different situation, but the one person in the class who’s older than I am told me that she would like to start working again, and the hours needed each day for the course don’t allow for finding a good job. She’s Ukrainian, and she shared with me that she’s from Kiev and that she and her daughters felt like they needed to leave three years ago, soon after the Russian invasion. I presume that she waited this long in Prague before taking the Czech language course because she was trying to figure out how to survive, and she might have thought that she could return home to Ukraine safely again some time soon. Maybe she has accepted that she’ll probably be in Czechia for some time longer, so it will be good to learn the language, at least as a start. I read last week that according to the Interior Ministry, there were 364,600 Ukrainian refugees with temporary protection living in Czechia as of March. That’s an amazing statistic – this number reflects only those Ukrainians in this one particular small country. Each one of these Ukrainians has their own story. I must add here that as sad as this all seems, the three Ukrainians in my class are all very pleasant, cheerful, and polite, and very quick to smile. They seem to be making the best of an unplanned and unfortunate situation.

I admire their fortitude. I doubt that I come off as content as they do, so they provide a good reference point to me. In this course, this is the most times I’ve ever answered so many questions incorrectly in one course in my life, by far. Probably multiple orders of magnitude more. And I often catch myself becoming frustrated, but I just need to remember to listen to the lightness and the frequent chuckles of the Ukrainian ladies to get a reminder to not take it all too seriously.

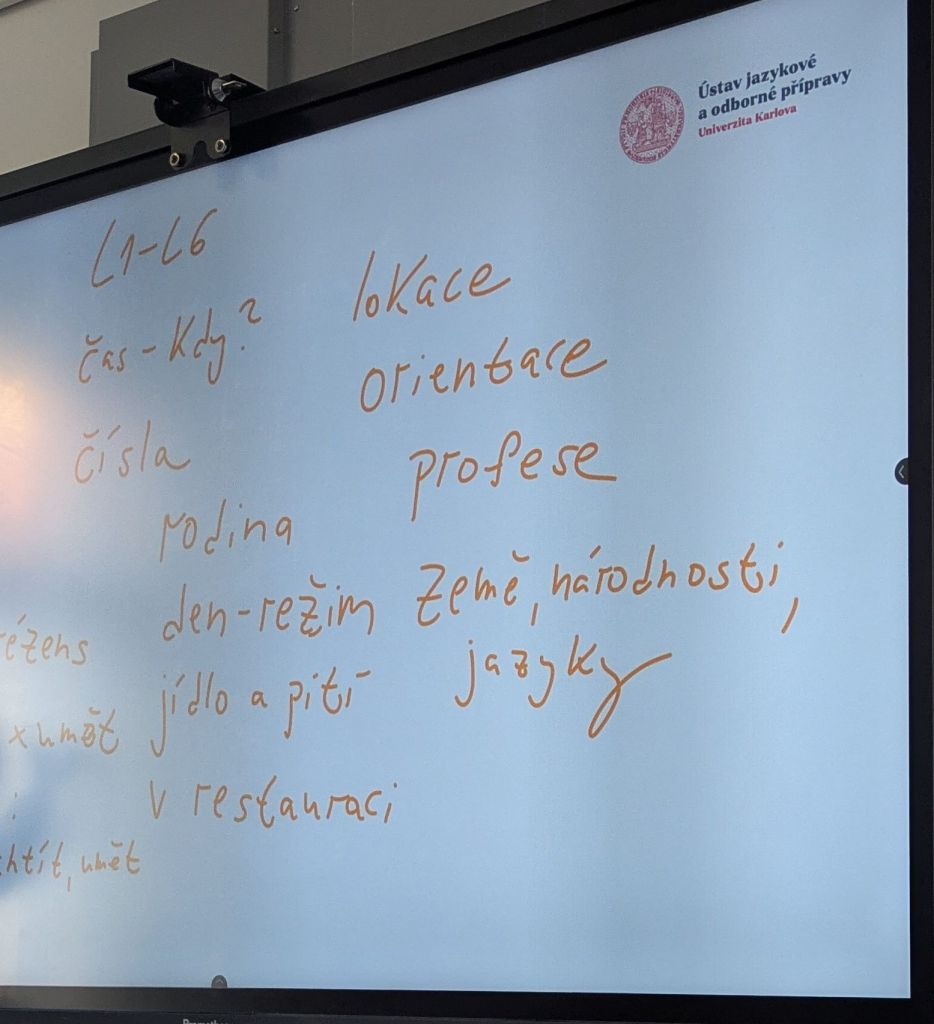

We had our course exam on Tuesday, but it’s really just for our own benefit – there is no official certification other than for participation. Here are some of the topics we learned in the first six lessons which could be covered in the exam:

Totally coincidentally (this story was on a recent general trivia podcast), I learned that the actor Daniel Day-Lewis learned Czech in preparation for his role in the movie “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, but that the role was totally in English, and his faux Czech accent wasn’t accurate anyway. The following summary is from an Englishman living in Czechia, with whom I can empathize:

Everyone knows Daniel Day-Lewis is one of the most meticulous method actors in cinema, and there are plenty of wild stories about how far he is willing to go in preparation for a role.

…

It’s all part of the Daniel Day-Lewis legend and, whether you think it’s over the top or not, his dedication to getting himself in the right space physically and mentally for a role has translated into a shedload of awards and a reputation as one of our greatest living actors. Some of Day-Lewis’ Method prep must have been grueling, but arguably his toughest (and potentially unnecessary) feat was learning Czech ahead of his role in “The Unbearable Lightness of Being.”…

I’ve lived in the Czech Republic for 13 years now and learning the language has been an absolute nightmare. I took lessons for a few years but very little stuck, and even now I am only able to fumble through the most basic interactions.

https://www.slashfilm.com/912816/daniel-day-lewis-admitted-his-method-acting-missed-the-mark-in-the-unbearable-lightness-of-being/

As you well know by now, which I’ve reiterated ad naseum, Czech is tough. When I learned Swedish and then Spanish, understanding and memorizing the names of the months wasn’t challenging because of the similarity of those names. Januari, februari, mars, april, maj, juni, juli, augusti, september, october, november, december in Swedish. How about that for being similar (or even the same), other than lack of capitalization. And in Spanish: enero, febrero, marzo, abril, mayo, junio, julio, agosto, octubre, noviembre, diciembre. A bit different, but recognizable except maybe enero. These month names across languages are reflective of the Roman deities, along with numbers (for the previous 10-month year system).

But in Czech? Of course not, haha. Here are the months in Czech, in the same order: leden, únor, březen, duben, květen, červen, červenec, srpen, září, říjen, listopad, prosinec. The focus with these names is on nature, with some month names having clear origins, while others remain somewhat mysterious. For January (leden), “led” is “ice”, and for November (listopad), “listopad” reflects a falling leaf. This naming convention is pretty cool, though definitely tricky to remember, at least in these early days.

Czech is not the only language, even in Europe, which doesn’t reflect the Roman month naming system. Ukrainian and Croatian don’t either, for example. But Slovak, Serbian, and Russian somewhat surprisingly do use the Roman naming system. As do many other languages too, even those whose speakers are mainly based far from the former Roman Empire – here are just some examples for the month of November:

– Arabic (Egypt, Morocco, and some others): نوفمبر (nūfambar)

– Azerbaijani: Noyabr

– Bulgarian: ноември (noemvri)

– Dutch: november

– Estonian: november

– Fijian: Nooveba

– French: novembre

– German: November

– Greek: Νοέμβριος (Noémbrios)

– Greenlandic: novemberi

– Hebrew: נובמבר (nôvember)

– Hindi: नवंबर (navambar)

– Hungarian: november

– Indonesian: November

– Latvian: novembris

– Malay: November

– Somali: Nofeembar

– Swahili: novemba

– Tagalog: nobyembre

– Tajik: Ноябр (Noâbr)

– Tamil: நவம்பர் (Navampar)

– Urdu: نومبر (novambar)

– Uyghur: نويابىر (noyabir)

– Uzbek: Ноябр (Noyabr)

– Zulu: uNovemba

And Czech? Oh yeah, listopad. And because it’s Czech, the names of the months themselves change based on the context in which they are used. So in English, for example, for the month of August, we’d say “August 2” for a date, or “in August” generally. In Swedish for the same, it’d be “2 augusti” and “i augusti”. In Spanish, it’d be “2 de agosto” and “en agosto”. In none of these three languages does the month name itself change for the different situations, because none of these languages includes cases. But Czech does, and so for the month of “srpen”, there’s “2 srpna” and “v srpnu”.

Today’s Prague insights:

Czechs have a bit of a reputation for being relatively cold people, but strangers here have a wonderful custom of saying hello and goodbye in elevators, doctor’s waiting rooms, train cabins, etc. In shops and restaurants, the staff will do the same, but I recall being surprised by other clients also saying hello and goodbye in waiting rooms. I really appreciate it. People don’t make a big deal about it, and there’s not normally any small talk or chit-chat, but just genuinely friendly “dobrý den” upon arrival and “na shledanou” upon departure.

One recent Czech public holiday fell on Thursday, May 8, which was Liberation Day. This year marked the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Czechia by American and Soviet forces. The Americans famously liberated the city of Pilsen, while the Soviets liberated Prague. In just the few days before, Czechs kicked off what’s now called the Prague Uprising.

On May 5, 1945, following six years of Nazi occupation and with the end of the war on the horizon (Adolf Hitler had killed himself in his bunker a week earlier), the Czech Resistance in Prague revolted against German forces during what became known as the Prague Uprising.

The Nazi occupiers responded by taking Czech civilians hostage, using them as human shields and executing them en masse; pregnant women and children were among the victims, most of whom were killed on May 7 and May 8.

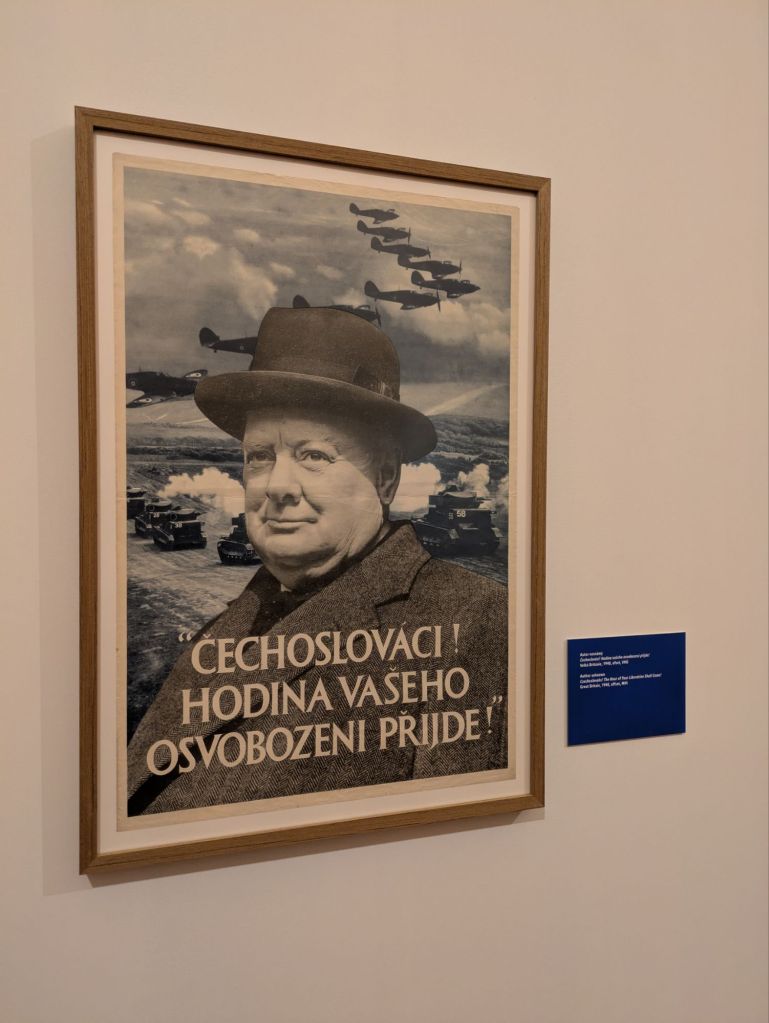

While the city of Prague, unlike many other major European capitals, had survived most the war unscathed, it was heavily damaged during the Prague Uprising, which saw German tanks fire recklessly into buildings on the streets of central Prague.While British Prime Minister Winston Churchill encouraged the liberation of Prague by US forces – US General George S. Patton’s Third Army had already entered Czechoslovak territory – Allied Commander (and future US President) Dwight D. Eisenhower gave in to Soviet pressure and kept US forces out of the city.

https://www.expats.cz/czech-news/article/on-may-8-the-czech-republic-remembers-the-end-of-wwii

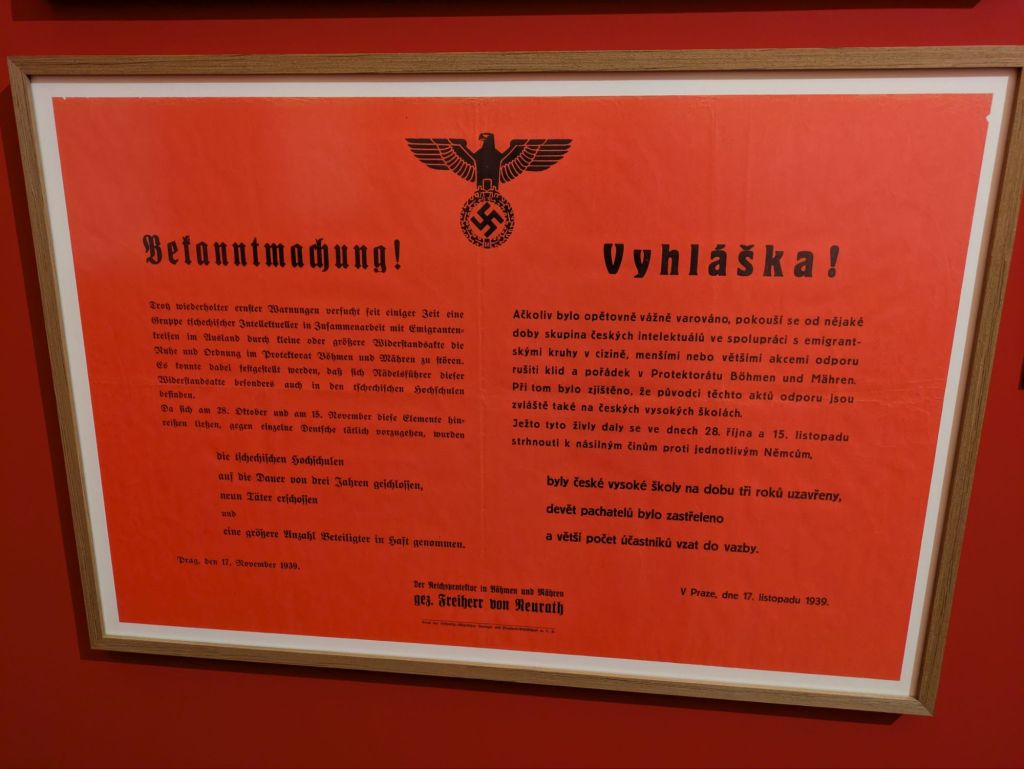

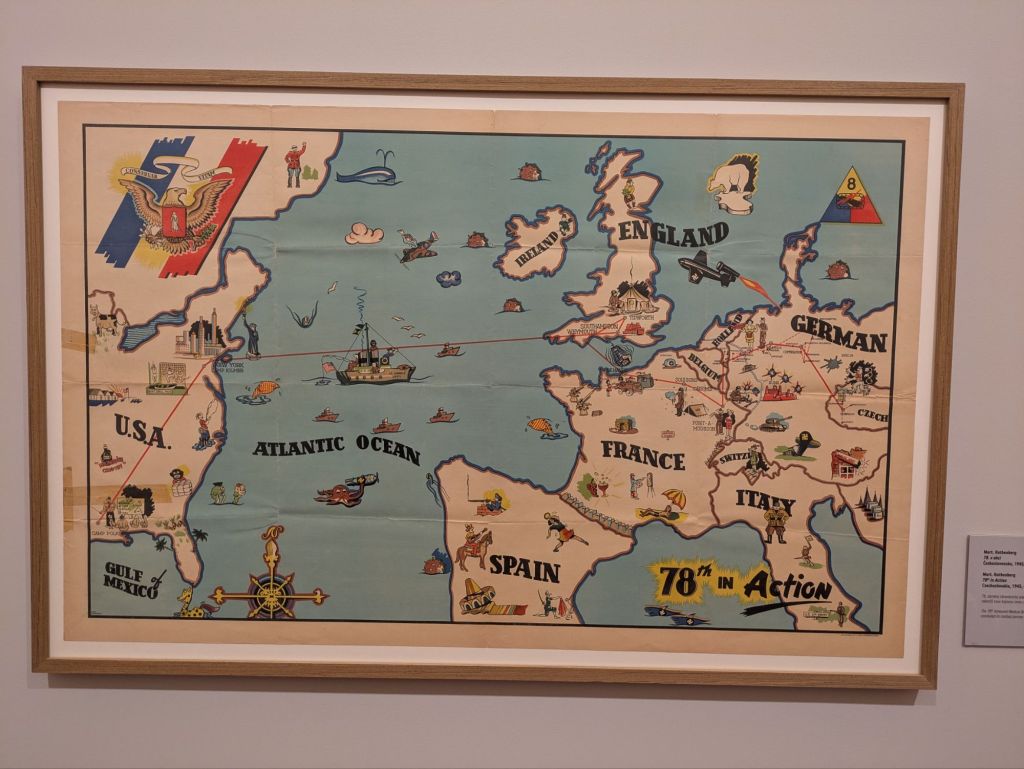

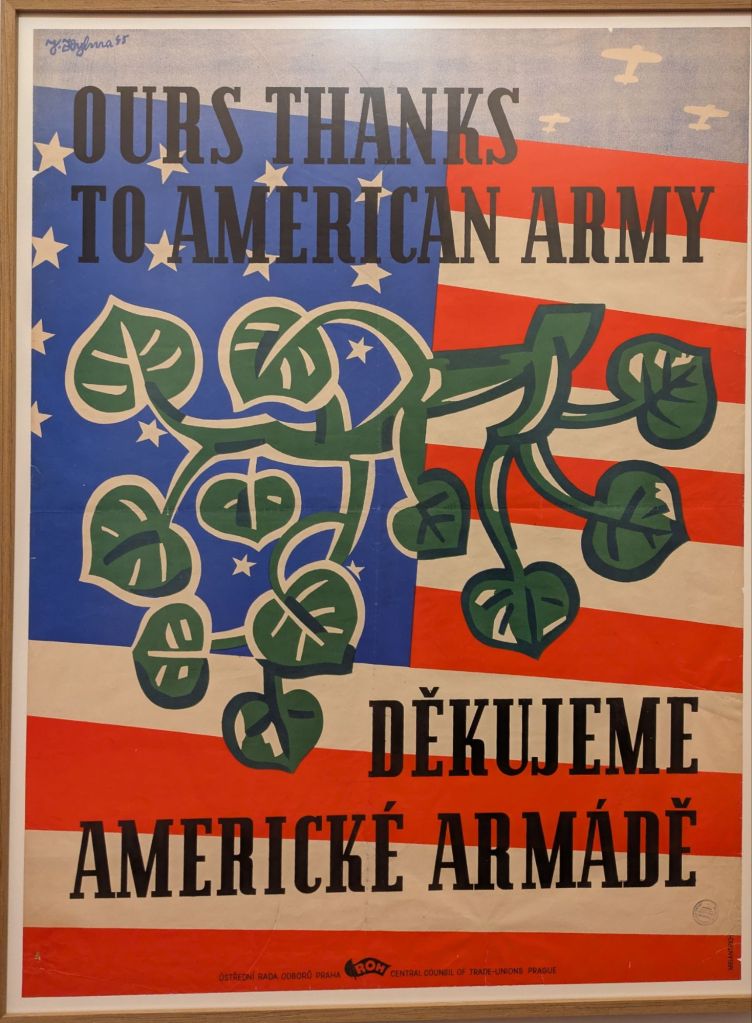

Sofia told me about an exhibit on Old Town Square where there were bleachers and a screen set up to show images from the uprising and the destruction of buildings around the square. It was a somber experience watching these scenes. Then on Saturday I went to the Prague Castle to the Imperial Stables where there was a free exhibit of around 100 posters from just before and during World War II from various countries, including Germany, Czechoslovakia, the United Kingdom, the USSR, and the United States. All very fascinating, and I cannot seem to get enough, because I always learn something new. In this exhibit (which almost all the hordes of tourists somehow overlooked) there were also artifacts associated with the assassination of high-ranking SS official Reinhard Heydrich in Prague.

* From the Nazi decree from above:

Although serious warnings were given again, for some time now a group of Czech intellectuals, in cooperation with émigré circles abroad, has been trying to disturb the peace and order in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia with smaller or larger acts of resistance.

In doing so, it was found that the originators of these acts of resistance are especially also at Czech universities.

Since these elements could be drawn to violent acts against individual Germans on October 28 and November 15, Czech universities were closed for three years, nine perpetrators were shot, and a larger number of participants taken into custody.

The Reich Protector in Bohemia and Moravia, signed Baron von Neurath

In Prague, on November 17, 1939.

Today’s Prague (and surroundings) photos:

On a much lighter and modern note, what a ridiculously beautiful place this region is…

Today’s DadGPT joke:

I made a pencil with two erasers…

It was pointless.

Today’s Japanese video:

Colleen and I have enjoyed all of the many videos that Paolo from Tokyo has produced on YouTube. We particularly enjoy his behind the counter series, like this episode at an onigiri shop. Here’s a convenient link to the entire behind the counter series.

Today’s Epictetus:

He who is not happy with little will never be happy with much.

Well done! The detail provided really gives one a deeper sense of your experience, and an appreciation for your sense of adventure.

Thanks for the feedback! Colleen told me that I sound lighter and happier in this post, and I definitely am feeling that way. I had a month-long medical issue that I had minor surgery for, along with four other doctor visits over weeks during recovery. I finally feel better over the past few days. And now the class is almost done, I finished a couple of big work projects, and I feel settled in, doing many group activities with new friends in the past week, like a birthday party at a darts bar, an astrophysics pub quiz, two 10km social runs, and a 24-mile hike. There’s so much fun stuff to do here!!