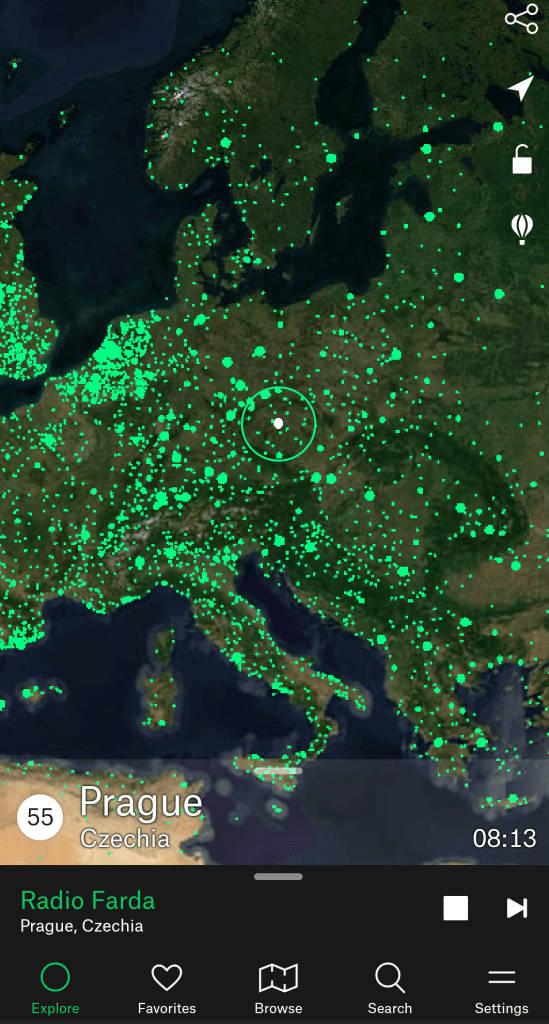

60% done now – 18 out of 30 sessions completed! It continues to amaze me how much we learn each day, and how the more I learn, the more complex Czech seems. In class on Friday I just had to chuckle aloud when the teacher showed us all the various word ending changes and rules for the locative case (location-based). And we only learned the singular form, not plural! I can see why it takes years to get this all down. For example, from the textbook: “Nouns of foreign origin and nouns ending in h, ch, k, r, or g, only have the -u ending. If the last consonant of the word is d, t, n, b, p, v, m, or t, the ending is not -e, but -ě… Feminine nouns from the first declension group which end in -ha, -cha, -ka, -ra, -ga undergo a consonant change before the ending.” And so on, and so on… Makes me sleepy just looking at it again now. It’s times like these that I feel like waving a white flag of surrender. I’ll never possibly get all those endings right. I know someone whose girlfriend is Czech, and he just uses the nominative form of words with her family, and they get it based on word order and context. That to me seems very practical, allowing for time to build much-needed vocabulary instead of memorizing which letter(s) to put at the end of each word for correctness for all the various cases.

Speaking of surrender, I’ve been telling people that I’ve bitten off more than I can comfortably chew with the several hours of Czech language work per day plus my consulting work. I’ve been told by some that I could just quit the class. I’ve already learned a good amount, and it would free me up. As tempting as that is, I’ve committed to this (and paid for it), and I want to see it through. I’ll reap the benefit through being able to read and understand much more Czech (and other Slavic languages), and it will have been quite a memorable experience. Plus, it’ll be over before I know it, and I’ll suddenly have 7 extra hours per weekday, for which I’ll be extra grateful!

From “Culture Shock Czech Republic”:

… you are up against a monstrous task, for Czech is an extraordinarily complex language that takes incredible patience and stamina to learn, and even Czechs themselves readily acknowledge this. Many foreigners living in Prague become so intimidated by it that they quickly give up. This is undoubtedly compounded by the fact that many are too busy with their daily jobs, family and social calendars to really apply themselves to the task, and also because so many of the Czechs they meet are eager to improve their command of English. As understandable as this is, keep in mind that your standing is raised a thousandfold if you are able to communicate with Czechs in their own tongue.

Because Czech is so difficult, and because it is (unfortunately) so insignificant outside of the country itself, Czechs are extraordinarily receptive and appreciative of anyone who make the remotest attempt to acquire even a basic vocabulary. The utterance of even a few random words is invariably met with, “Oh! You speak good Czech!” which is wonderful for the ego but can easily lure you into a false sense of security.…

It takes a lot of textbook work to make headway; Czech is not a language that you can simply ‘pick up’ without systematic study.

…

Even Czech children need to be formally taught the nuts and bolts, as well as pronunciation, before they are able to use it properly.

The course teacher has been quite accommodating when I’ve had to miss a part of class a couple of times, messaging details to me afterwards of what I missed, in English! She so rarely uses English during class that it’s refreshing to get it in writing from her anyway. But I tell you, it’s quite common for her to explain something in Czech, like a task for the students, and I just cannot understand. I feel like a dummy when she asks if everyone understands, and people say “ano” (yes), and I’m embarrassed to be the odd one out, figuring I’ll wing it and maybe ask one of the other students. But on many occasions we gather in teams to begin one of the described tasks, and I ask someone who answered “ano” to understanding what the instructions were, and that other student replies “I’m not sure!” So they just pretended like they understood, haha. Since then I’ve been forthright when I don’t understand something when everyone else says they do because I know that in reality they might not. I’ve also found that sometimes other students say they understand, and they believe they do, but in fact they misunderstand instead.

Speaking of these students, I’ve run into some of them out in the city. In fact, I’ve run into multiple people I know over the past few weeks, and I don’t know very many people here! I figure it must be because of public transport, where we’re all on foot or in some type of carriage together. One day on the way to class in a tram someone tapped me on the shoulder – it was my visa agent on her way to work. Thrice one of my running buddies has suddenly shown up at my side, and I’ve run into one fellow student twice in different places in the city. Another classmate said she saw me running by in a park. During a break one day during class, I was walking down the sidewalk when someone came alongside me and gave me a not-insignificant push. I turned to see what other friend was signaling their presence, but in that case it was just a drunk guy indicating his impatience to pass me. He looked sort of familiar though, so it took me a while to figure out what had happened. I thought about catching up to him and asking “what the heck, dude?”, and maybe even pushing him back, though then I remembered the words of Epictetus (see bottom of post) and moved my mind on to something else. But no kidding, later that week during one of my group runs, I ran past that guy in a different part of the city, and this time he was smiling, giving me a peace sign.

Before the run that particular evening, on my way to meet up with everyone, I was early, so I was a couple of blocks away stretching when a guy approached me and asked something in Czech. I asked him in Czech if he spoke English, and he complained in English, with a smile, that he has trouble finding people that speak his language in his own country. I was able to help him with directions, as he didn’t have a phone, so I pointed him to the street he was looking for on Google Maps. Five minutes later when I showed up at the group meeting point, there this guy was to join our run! I’m glad I was nice to him, haha. He and I chatted for much of the run – he was an interesting chap. He said that he’s been detoxing from his phone because he finds himself addicted to the apps and social media. When I told him I was learning Czech, he definitely softened. He told me that Czechs historically intentionally made Czech difficult so they could keep secrets from the Germans. I suppose that’s just apocryphal, but I can see why the story sticks, especially given the Nazi history here.

Regarding that Czech learning, I find it rather ironic that the Czechs, who are otherwise so logical, would use double negatives in their language to be negative. “He never drinks Becherovka” translates as “Nikdy nepije Becherovku”, “nikdy” being “never”, and “nepije” meaning “he doesn’t drink”. So it means “He never doesn’t drink”, which seems to me like it must mean that he’s drinking Becherovka all the time!

Clearly that’s not right. But what about “right”? Have you ever considered that the word “right” pertains not only to direction, but also to correctness? At least in English? But this is also true (right) in Swedish (“rätt”). There’s also something to which one has a just claim, like a human right. In Spanish the word “derecho” serves at both direction and something to which one has a just claim. And in Czech I’ve learned that very similar words are used for direction, correctness, truth, and something to which one has a just claim: “vpravo”, “pravy”, “pravda”, “právo”, etc. It seems to show a right-hand bias in culture and society at large. Think of Latin’s “sinister”, which originally meant “left,” but came to mean threatening or malevolent.

Here are some other tidbits I’ve learned from studying Czech:

Like other Slavic languages such as Russian, Czech doesn’t normally leverage articles like “a” or “the”, and so Czech speakers tend to get confused as to when to use articles in English, so these articles often just get thrown into places where we wouldn’t actually normally have them in English. For example, see this recycling bin in the university building:

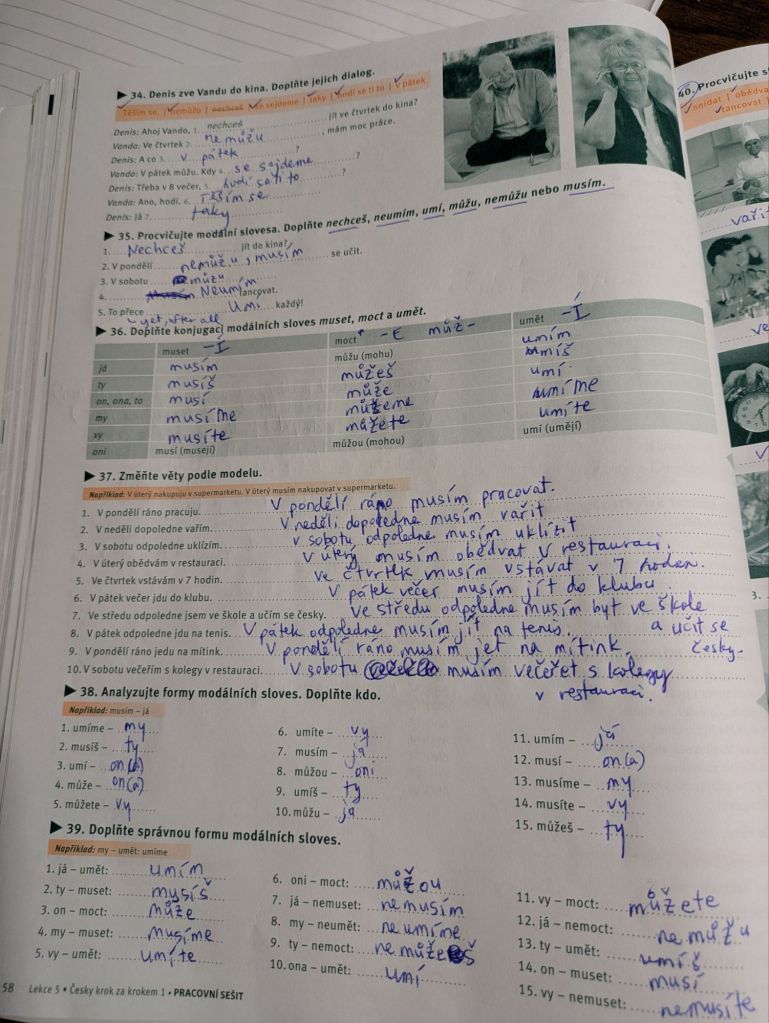

Even possessives have to be overly complicated in Czech. In English we simply add an apostrophe plus ‘s’, like “Scott’s shoes”. In Swedish it’s even simpler, without an apostrophe: “Scotts skor”. In Spanish, one uses “de” (“of”) to show possession: “Los zapatos de Scott”. So there the name doesn’t get changed at all. (Speaking of extra articles, Spanish loves them articles.) So how about for Czech? There needs to be a table for that, of course, for all the different scenarios, like whether the possessor is male or female, along with the gender of the thing they’re possessing:

I snicker a bit each time the teacher says “Odkdy dokdy” (“from when, to when”).

I can’t believe I haven’t discussed the Czech letter “ř” yet! From the “Culture Shock Czech Republic” book: “There is one letter, ř, which is so difficult that even children have to be taught properly how to say it. It’s a hard r, rolled but once, followed immediately by zh; it’s all one sound, and it comes out like a crash of glass. This letter only appears in the Czech language, a fact that many Czechs are perversely proud of.” I’ve heard it sound different from different people and in different words. Our teacher seemed to instruct us to roll the r more than once. I’m not sure if it’s actually hard to say, or if it’s just that it’s said differently in different situations so that learners have a hard time using the right sound at the correct time. I don’t know, but I’ve been understood when I say words with it, so I guess I’m saying it well enough! My model is the Czech composer Dvořák’s name, where the ř sounds exactly like the book describes it above.

Going back to Czech cases, I had mentioned in the previous post (week 3) that word order is leveraged in English to indicate parts of the sentence – English uses subject-verb-object (SVO) order in the active voice, like “The lion ate the deer.” In Czech the word endings indicate the sentence parts, so order is flexible. This means that “Lev sežral jelena” is effectively the same as “Jelena sežral lev” (“The lion ate the deer”), but “Lva sežral jelen” means that the deer ate the lion. The word endings (or more than just endings!) indicate the case, whether each noun is the subject or the object of the sentence. The verb stays the same. That said, English does have what’s called the passive voice, where the object can come first: “The lion was eaten by the deer”, but here the verb form changes, and a preposition is added so as to indicate who’s performing the action.

Someone asked me this week why I came to Czechia to learn Czech instead of learning it back home. Uh, because AB-Tech hasn’t added Czech to their curriculum yet?

Today’s technology tip:

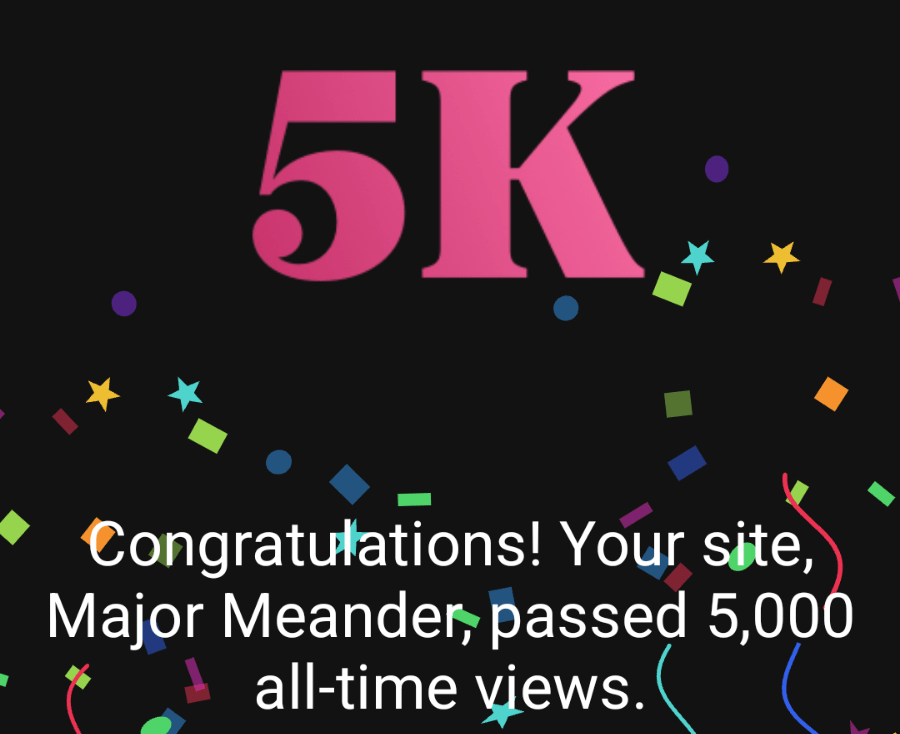

Here’s a fun way to virtually travel: use the website Radio.garden to find and listen to radio stations from all over the world. It’s also interesting to see radio station density by area on the map.

Today’s Prague insight:

Some folks have asked me where I’m staying during the weeks of the Czech immersion course, and how I found it. I’m staying in an apartment a bit farther out, but easily reachable by tram from downtown. I found it via a lodging marketplace platform called Flatio, a solution similar to Airbnb, but concentrating on mid-term rentals. With weekly or monthly stay discounts at some properties with Airbnb it’s possible to get a really good price for longer rentals, but I found that Flatio was more competitive. I believe Flatio’s focus is in European markets. These rentals are furnished, but there’s a rental contract process that I found much more formal than what one experiences with Airbnb. It was risky to commit to two months at an unfamiliar place, but there were good reviews, and with the platform one can back out with cause if the apartment isn’t what was listed. I really like my place, especially since it’s so very quiet! I’m continually amazed at how quiet a place in a big city can be.

Thanks to all you readers! WordPress let me know of this recent milestone:

Today’s Prague photo collection:

Today’s dad joke:

Why did the baby ape start imitating his dad’s banana-peeling skills?

Because he’s a chimp off the old block!

Today’s Japanese video:

It’s no wonder that Japanese folks can stay so healthy. Look at what they are served for lunch at schools! Setting the stage for future good habits. Quite a contrast to a typical school lunch in the US, one must admit. I recall one of my classmates in elementary school eating napkins drenched in ketchup for lunch. Hopefully that was a one-off.

Today’s Epictetus:

Any person capable of angering you becomes your master.

Another fascinating and detailed post, Scott! I was telling Matt and Michigan Todd yesterday about your blog, and forwarded them the link. Hopefully they’ll take a look, and maybe they and I can discuss it. Not sure that I’ll know how to explain declensions, but I’ll give it a whirl, okey dokey? Joe

Thanks! I miss hiking with y’all! I look forward to doing so again this summer. Say hello to Matt and Michigan Todd, along with the rest of the crew, from me. 😁