The Icelandic language retains more of a relationship to Old Norse than do other Scandinavian languages, such as Norwegian. Modern Icelanders can even read the old medieval sagas without too much trouble. Their language hasn’t evolved as much as other Scandinavian languages which were influenced by other European languages, such as French. And even today, a modern foreign term will normally be described with a newly-constructed Icelandic compound word. That said, there are some interesting expressions that seem related to English or at least originate from common Germanic language roots. For example, “hæ” is pronounced as “hi”, and it has the same meaning. Similarly for “bæ”. My favorite Icelandic expression is “bless bless” for “bye bye” — I heard this one a lot.

In preparation for this trip, I studied Icelandic for about an hour per day for four weeks using Pimsleur, since neither Duolingo nor Rosetta Stone offer Icelandic lessons. One thing I learned through that process was about the “th” letters eth (Ðð) and thorn (Þþ). The first is voiced (uses the vocal chords), while the second is voiceless. We might at first think (voiceless) that (voiced) we don’t use both voiced and voiceless “th” in English, but clearly we do. Most main European and Asian languages lack either “th” (dental fricative) sound, and speakers of those languages often have a surprisingly difficult time making these sounds, which native English (and Icelandic) speakers find so straightforward.

Icelandic retains a somewhat complicated case system whereby word endings change depending on usage in a sentence. One must decline (change) pronouns, nouns, and adjectives in four cases (subject, direct object, indirect object, possessor). English retains a little bit of a case system for pronouns, such as he, him, and his, but not for adjectives and nouns (other than to change, usually just a little, for plural or possessive). Whole proper names don’t change in English, but they do in Icelandic based on the case system. Iceland has a Personal Names Committee that controls what first names parents can give to their children from a list of around 3500 approved names. This is used to ensure that these first names will work within the Icelandic language case system. But as more foreigners have been arriving with their non-approved and noncompliant names, there is pressure to abolish this committee and constraint. Our Dominican immigrant tour guide in Reykjavik was very clear that he thought this system was dumb, and he didn’t appreciate the rules for naming when his and his Icelandic wife’s children were born.

But children don’t have to even have a name for up to six months after they are born, which is similar to Sweden, where our friends would take their nameless newborn home from the hospital, only to announce the given name some weeks or months later. And these first names are what everyone is called by — there’s no “Mr”, “Mrs”, “Miss”, or “Ms” in Iceland. There’s an inherent formality to a first name, as most Icelanders go by a nickname with family and acquaintances. For example, when working for OZ, I had an Icelandic coworker whose given first name is Haraldur, but he goes by “Halli”.

In any case, getting around Iceland was super-simple given everyone’s excellent English. Some folks had pretty strong accents, but their English was very good, and they always understood us right away. We overheard an Icelandic store worker chatting with her romantic partner in English, and staff at other shops and restaurants often spoke to each other in English. This was presumably because there are numerous foreign workers in Iceland, particularly during the tourist rush in the summer season. I spoke to a lady in a restaurant in a town of 300, and this lady was from a small town in Slovakia!

At this restaurant and others, while there were plenty of “typical” options like sandwiches, pastas, pizzas, and/or burgers, there were often also Icelandic dishes, sometimes just for the associated tourism novelty, such as fermented shark. We read about (but I didn’t see) puffin and whale being served to eat too. There was certainly plenty of dried cod fish in the grocery stores — it is essentially fish jerky, almost completely protein and salt.

Another common offering in grocery and convenience stores is licorice, in many different forms. Icelanders love their licorice!! After having lived in Sweden for some time, I’m into licorice too, so I enjoyed a few types, and I surprised myself by finding chocolate-covered licorice to be delicious and addictive.

This is the final installment from our 10 days in Iceland, so here are some photos from our South Coast experiences. I hope you’ve enjoyed these posts!

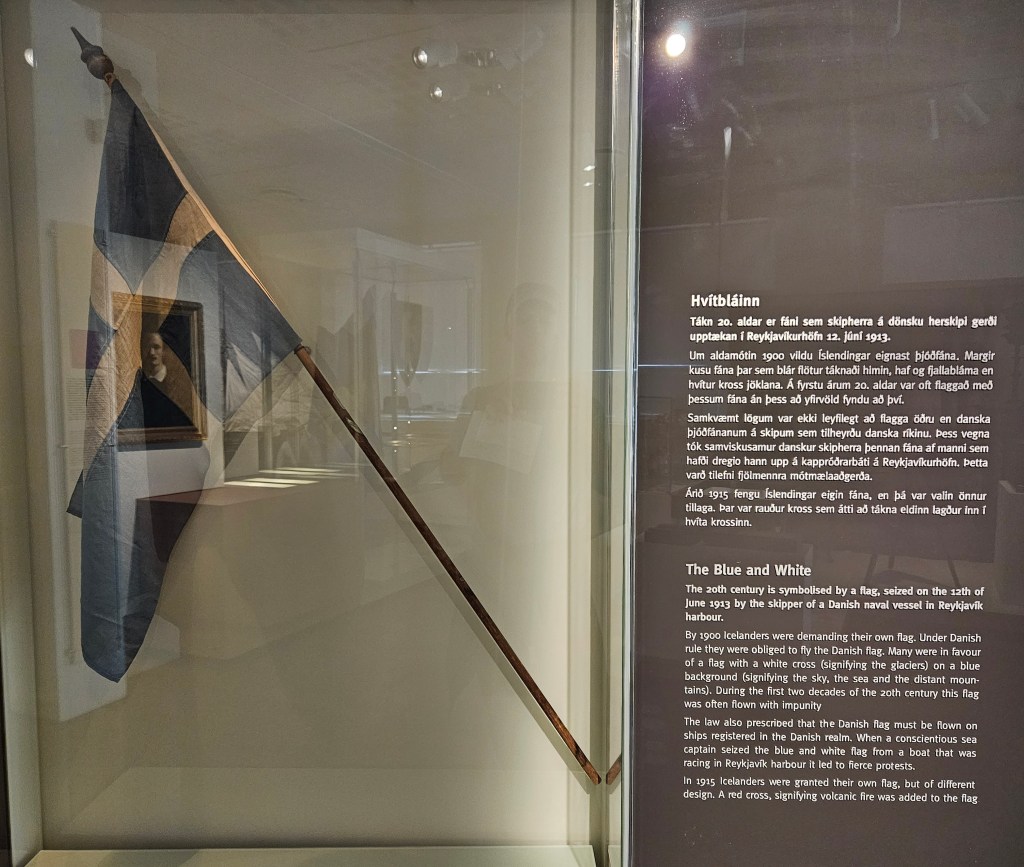

Icelandic side note: The Icelandic flag as originally designed had a blue background with a white cross, but sailors reported that this flag was difficult to distinguish from the Swedish flag from afar. Therefore, a smaller red cross was added on top of the white cross, making the Icelandic flag as used today. The current colors represent the sky, glaciers, and volcanoes — you can guess which color is for which.

Icelandic music videos: Iceland has an outsized English-language music scene, with acts popular worldwide. Here are a couple you’ve likely heard of.